Hunting Warhead

- Details

- Category: Paedophile Police

- Created: Wednesday, 18 December 2019 04:50

- Written by Daemon Fairless, Mark Gollom and Chris Oke -

In 2016, a Norwegian journalist and an ethical hacker went looking for the operator of the world's biggest child abuse site. The truth was more twisted than they even imagined.

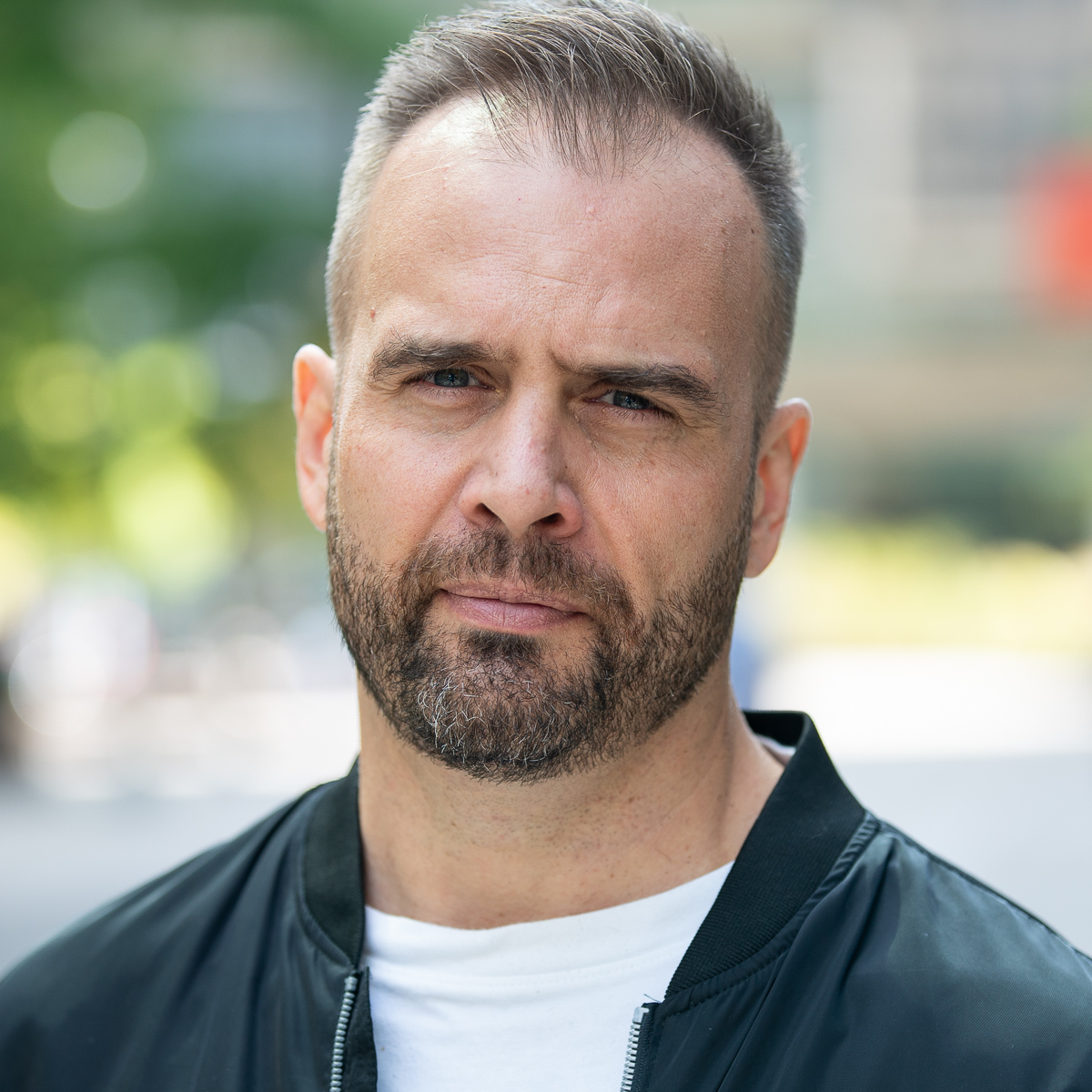

Oslo-based journalist Håkon Høydal and computer expert Einar Stangvik spent a year on an exposé about Norwegians who visited child pornography web sites. The story, published in 2015, was a blockbuster.

But their next big project was an even more twisted tale — and it led them to stumble upon the operator of the world’s largest child abuse site.

Back in 2013, Høydal, a reporter for the Oslo tabloid newspaper Verdens Gang — popularly known as VG — had teamed up with another reporter for a story on revenge porn, and how Norwegian law enforcement was falling short in stopping it. These are sites that post intimate, personal pictures of women that have been stolen from their accounts by anonymous internet trolls who are often ex-boyfriends.

That VG article caught the attention of Stangvik, an internet developer and hacker who had been conducting his own investigation into revenge porn.

Stangvik had built a system that could monitor different sorts of shady forums for newly posted images and download the metadata from these images. That metadata would include information about the pictures — file names, when the shot was taken and the GPS coordinates.

Listen to the first episode of Hunting Warhead, in which Høydal and Stangvik track down the men behind Childs Play:

Stangvik had some criticisms of Høydal’s story and contacted the reporter. They struck up a friendship and eventually collaborated on a year-long project investigating child abuse materials being accessed by Norwegian users. They discovered more than 5,000 files downloaded by about 300 people.

Their stories had focused on sites found on the worldwide web, the so-called clear nets. But Høydal and Stangvik knew there was much more to be found on the dark web, a space for all manner of illicit activity — including the sale of credit card numbers and drugs — that can only be navigated through a specialized browser called Tor.

Høydal was reading one of the dark web forums when he saw some users mocking the people who had been identified in his VG story about Norwegian men downloading child porn. One user called them losers, and insisted that the dark web was safe for pedophiles.

"It was really a middle finger to our work … you know, just ‘F--- you, and you won't be able to find us,’” said Høydal. “So we took that as a challenge."

Stangvik created a few different user accounts on a variety of child abuse sites. He configured his browser settings so he wouldn’t have to see the images, but could still read the text and comments on these pages.

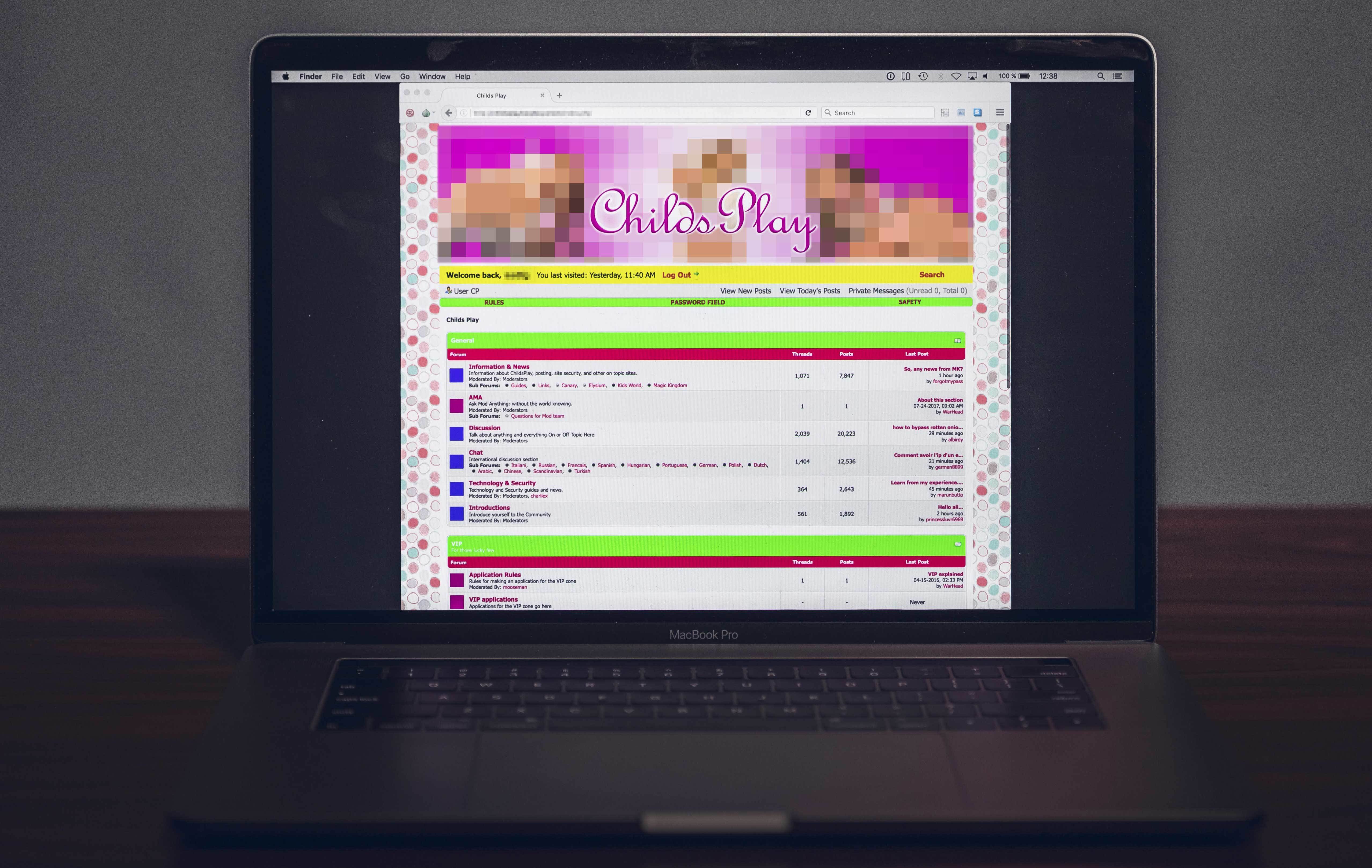

He identified a few of the most popular sites, but one stood out: Childs Play, which had a million registered user profiles, and was run by someone with the username Warhead.

During the fall of 2016, Stangvik monitored the site and the messages being posted there. A few months in, he made a significant discovery: Like many web sites, Childs Play allowed individuals to upload an image for their user profile. But if an image in a user profile originated somewhere on the clear net, Childs Play’s software would reach out and look for it, sending a brief signal from its hiding place on the dark web.

The signal was traceable and contained information about the server's IP address. It’s then that Stangvik figured out that the Childs Play server was located in Sydney, Australia.

Armed with this information, Høydal flew down to Sydney to meet with the owner of the hosting facility. He told the owner that a major child porn website was stored on their server, and that he wanted to find out who was renting it.

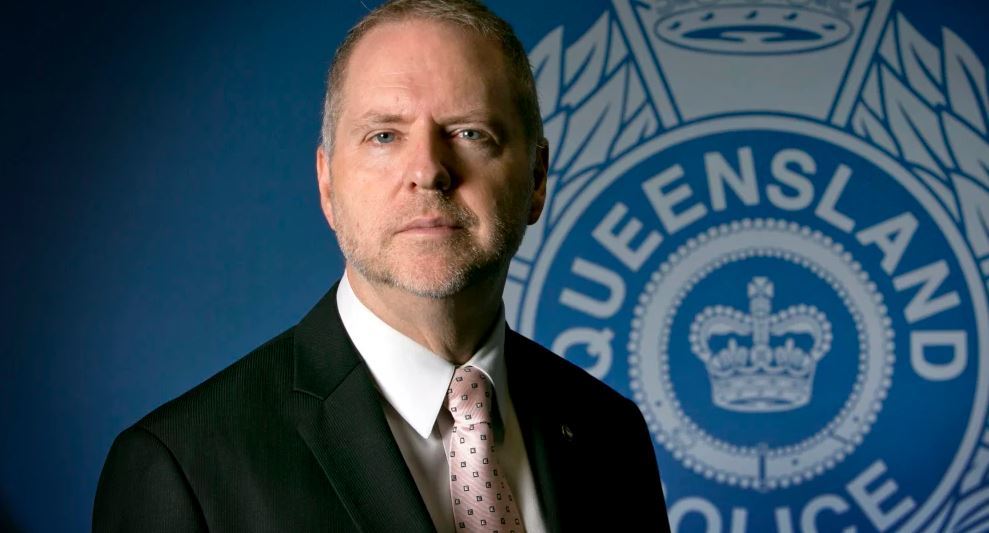

The owner quickly discovered that the server was being leased by a branch of the Queensland Police Service. Høydal contacted them, which led to an uncomfortable meeting between Høydal and members of the police unit, Paul Griffiths and Jon Rouse, in a Brisbane burger joint.

After Høydal told them that he knew they were running Childs Play, the two officers suddenly went silent.

"[Griffiths] just turns purple and quiet," Høydal recalled. "And Jon, the other guy, he turns completely white and gets real stiff and upright and stern and says, ‘We're not going to discuss this anymore until I know how you have found this information — how you knew it was us.’"

‘All of a sudden, I find out that Warhead is the police’The officers’ nervousness was not due to guilt — it was because their cover had been blown.

"I'd gone down to find out who Warhead is,” Høydal said. “And all of a sudden, I find out that Warhead is the police."

Well, not exactly. It’s just that the police had gotten to Warhead first.

II.

Benjamin Faulkner grew up in North Bay, Ont., which is about 350 kilometres north of Toronto.

He was, according to his mother, a happy boy, someone who was always friendly, well-liked, gentle and patient. His father said he had lots of friends in high school. Not a partier by any means, Faulkner was more of a gamer and obsessed with computers.

He also worked as a lifeguard and swim instructor, one of those teachers who kids would request by name.

If there was anything out of the ordinary about Faulkner, it was that he didn't have a girlfriend, his mother said. "I kind of thought that he was gay. If only that were the case."

Listen to Episode 5 of Hunting Warhead and learn more about Benjamin Faulkner's past:

As a young adult, Faulkner was into Dungeons and Dragons, and other than being a little nerdy, he was completely ordinary. His entire wardrobe was essentially black T-shirts and jeans, according to a former roommate who asked to be identified as "Gordon."

Faulkner was in his mid-20s when he and Gordon shared an apartment in Guelph, Ont., for several months in 2016. Gordon, who is a few years younger, said that overall, Faulkner was a pleasant guy to live with. He wasn’t noisy and kept to himself. That’s mainly because he was on his laptop all the time.

Faulkner made it clear that he was making money on the internet. Gordon had the impression it was something illegal — like a Nigerian prince scheme or some kind of hacking operation.

"[Faulkner] said things like, 'The less you know about what I do, the better, or I could go to jail,'" Gordon said.

One summer, on a trip to North Bay, Gordon made a joke that Faulkner was probably creating child porn.

"And he says, 'Gordon, that's really just messed up. As someone who's worked with kids, I care about kids quite deeply, and I really, really prefer if you just tried not to call me a pedophile.'"

* * *

There was nothing that outwardly indicated Faulkner had a dark side, but a close relative, who is being identified as "Jen," got what she called “weird little tugs” in her stomach when he came to stay with her and her family in the United States in July 2016. (CBC decided not to reveal her whereabouts to protect her family's identity.)

It was a good visit, she said. Faulkner would hang out with her eight-month-old and two-year-old, and with her husband gone for most of the visit, Jen and Faulkner would spend evenings together talking, watching TV.

By his side was one constant companion — his laptop.

"Anytime you got too close to him when he had his laptop, he'd grab the top and bend it towards his chest," Jen said.

One of those evenings, she decided to pry a bit, asking Faulkner what he was doing on the computer. He told her that he had created a forum, and he was the moderator. She said he was amused by his number of followers. He told her he would post puzzles and the first one to solve it would get a prize.

"It really amused him to have people rushing to … his command."He told her the prize was a picture he made — another puzzle that would lead to another puzzle.

"It really amused him to have people rushing to … his command,” Jen said.

Nothing about Faulkner's behaviour raised any real suspicions, but Jen did have a number of those weird little tugs. “When I get them, you’re damn right I pay attention, because there were a few that happened during that visit.”

For example, Faulkner wanted to give her eldest daughter a bath. Jen snuck up on them while he was bathing her, just to see how they interacted. Everything seemed totally innocent.

“If they were alone,” Jen said, “it was for 20 seconds.”

A few days later, Faulkner abruptly announced that he was leaving to go see his friend Patrick.

III.

“Patrick” was Patrick Falte, a Nashville native who Faulkner, under the name Curious Vendetta, had met on a dark web forum called Pedo Support Community, which was devoted to pedophilia.

Falte, who went by the username CrazyMonk, also ran the Gift Box Exchange, one of the most popular spots on the dark web for trading child abuse material. The site had 45,000 users and Falte was looking for a co-administrator with a background in cybersecurity.

In the fall of 2015, he brought Faulkner on board as his right-hand man. Before long, Faulkner wanted to start his own website, and in April 2016, he created Childs Play and a new moniker, Warhead. The site eventually garnered more than a million registered users, making it one of the largest on the dark web.

What he didn’t realize is that Gift Box Exchange and Childs Play had gained the notice of international authorities, who had reason to believe they were operated by the same people.

Faulkner had a day job in computer forensics and IT security. He had also worked as something called a penetration tester, which means a hacker who tests the vulnerability and security of websites.

Despite his technical skill and caution, Faulkner ended up making a significant mistake. While running Childs Play, Faulkner was still the co-administrator for the Gift Box. Around the summer of 2016, he had a technical problem with the site, and went to a forum for programmers on the clear net and posted a screenshot of the code that was giving him trouble.

An international group of law enforcement officers had been trying to figure out the identity of Warhead, and a group of Homeland Security investigators in Boston had also noticed a technical problem with the Gift Box Exchange. On a hunch, they started combing the clear nets for people seeking to fix that specific code. They eventually found Faulkner's question, and traced it back to his IP address.

Meanwhile, CrazyMonk had also made a mistake. To pay for hosting for Gift Box Exchange, Falte had used bitcoin, the virtual currency that's supposed to be impossible to track. However, CrazyMonk had registered his bitcoin wallet to a personal email address, which Homeland Security investigators were able to trace directly to Falte. Through their online surveillance, authorities also discovered that Faulkner and Falte knew one another, and that they'd sometimes meet up in person.

And they knew it was just a matter of time before it happened again.

IV.

Late in the summer of 2016, Faulkner made an out-of-the-blue suggestion to his roommate Gordon: They should take a road trip to Washington, D.C.

Gordon agreed, and as they were nearing the nation's capital, Faulkner told Gordon that they would also be meeting up with his friend Patrick.

Gordon had arranged for accommodations at a relative’s home in the nearby woods of Virginia. Despite Faulkner’s sudden announcement of a third guest, there was room enough for all at the house.

What they didn't realize is that when Faulkner and Gordon crossed into the U.S. on Sept. 30, 2016, U.S. Customs and Border Protection alerted Homeland Security, which relayed the information to Canadian and Australian officials.

Faulkner’s entry into the U.S. also prompted Homeland Security officers to check in on Falte. Weeks before, they had attached a tracking device to his car in Tennessee. They found that he, too, was on his way to Washington in early October, and realized that Faulkner and Falte were going to meet up.

Homeland Security agents tracked Falte’s car to the Virginia home of Gordon's relatives, and when they saw that Faulkner’s car was also there, they put in a request for a search warrant of the house. The agents then spent the next days watching them.

On Oct. 1, Faulkner told Gordon that he and Falte had to go off and do something and wouldn’t be available again until the following afternoon. Oct. 1 happened to be Gordon’s 22nd birthday, and Faulkner gave him a wad of cash — around $300 — and told him to enjoy himself.

Faulkner and Falte left together in Falte's car. Homeland Security tracked the vehicle to a hotel in Manassas, Va. In the evening, the car was tracked to a private residence in Manassas, and then back to the hotel.

The next morning, Oct. 2, Faulkner and Falte left the hotel and met up with Gordon at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington. They later walked up the steps to the Lincoln Memorial.

The three of them eventually drove back to Gordon's relatives' place in Virginia to sleep. The plan the next day was for Gordon and Faulkner to head back to Canada, while Falte returned to Tennessee.

***

The following morning, just before 7 a.m., Gordon was awoken by the sound of the front door crashing down, dogs barking and people screaming.

"It was just pure shock. I had no idea what was going on,” Gordon said.

He peered out of the windows of the bedroom and saw the narrow driveway clogged with big black vehicles — police cars and FBI vans.

He opened the bedroom door and saw a man standing at the top of the stairs, holding a big gun. He told Gordon to put his hands in the air, and directed him to the wall beside him.

Looking into Faulkner’s room, Gordon said, "All I can see is Ben's face down on the floor. He looked like he was getting crunched by this big police officer who was on top of him restraining him."

"That was the last time I ever saw Ben."

Gordon himself was taken downstairs and handcuffed to a chair, as 15 to 20 police officers scoured the house.

The officers asked Gordon why he came to Washington and if he knew what Faulkner was doing online. They also stressed that there would be ramifications if he was withholding information or lying.

They asked Gordon if he had a computer (yes), if he had ever watched pornography (yes) and if he had ever watched child pornography.

“And I said, 'No, absolutely not.'”

The agent then asked if Gordon knew what Faulkner was doing the night he had gone out on his own.

"I said I honestly don't know what Ben was doing. And she said, 'Gordon, on Saturday night, Ben raped a four-year-old girl.'"

It was like the floor crumbled beneath him. Every conversation Gordon had ever had with his roommate had a new context to it.

And this is why Faulkner had wanted to go to Washington.

"It was a punch to the stomach, really," Gordon said.

During their search of the Virginia house, Homeland Security agents found a video camera Faulkner had brought with him from Canada, and they found a series of pictures and videos of a four-year-old girl being sexually abused.

Faulkner admitted to the abuse and identified himself in at least one of those images. The father of the girl, who was eventually arrested, too, had been operating the camera.

Online as Warhead, Faulkner had often boasted that if he was ever arrested, he would take every possible measure to keep police from accessing information about Childs Play and its members.

But upon being arrested, Faulkner gave it all up. Within minutes, he gave Homeland Security his usernames, passwords and encryption keys.

* * *

Shortly after Faulkner was apprehended, his relative Jen received a call from Homeland Security, who informed her that someone with whom she had a close relationship had recently been arrested.

She and her husband met with an agent outside a local diner near their home. Jen expected them to say that Faulkner’s hacking had landed him in some kind of trouble. Instead, one of the agents opened up a big manila folder, pulled out an image and said, "Is this one of your children?"

"And I was like, holy shit. What has he done?"

Jen was shown a series of photos including ones of their playroom floor, her baby's clothes, their toys, the house, the bathroom, bath mat and bath toys.

"Whoa, OK. Well, Ben's a pedophile."

The agents told Jen that they needed her to get her kids because they had set up an appointment with Child Protective Services for a forensic interview of her oldest child.

"How do you describe the moment your core is blown apart by another person?"When asked about this revelation, Jen said, “How do you describe the moment your core is blown apart by another person?”

But it wasn't over. Child Protective Services later asked Jen to book another appointment for her kids, this time for a physical examination.

They had received some new information: Faulkner had admitted to attempting oral sex with one of the children, and they needed to do blood and urine samples to check them for STDs.

Listen to Episode 4 of Hunting Warhead when 'Jen' finds out disturbing news about her relative, Ben Faulkner:

Hunting WarheadEpisode 4: Impact Statement47:50

V.

In September 2017, Faulkner was sentenced to life imprisonment for sexually assaulting the four-year-old girl in Virginia.

Two years later, he was sentenced to 35 years for engaging in a child exploitation enterprise. Falte had received the same sentence.

As the prosecutor read through the list of Faulkner’s online activities at the second sentencing hearing, the 28-year-old covered his face with his hand. His shoulders were shaking and it looked like he was crying.

But he had actually been laughing quietly to himself. Even after his lawyer told him to stop, it took awhile for the grin to vanish from Faulkner's face.

In court, he read a statement aloud, saying that for the first time in his life, he was speaking before the “people I love, about the wrongs I’ve committed.” But the statement was almost entirely about him, about his suffering, how he had had no option but to hide his desires from the world.

Faulkner said he was sincerely sorry for the people he had hurt, for the lives he had altered. He ended by saying, “If I could go back, things would be different.”

Daemon Fairless, who interviewed Faulkner several times by phone from prison for the CBC podcast Hunting Warhead, believes Faulkner said what he thought the judge wanted to hear — and that it didn’t square with what Faulkner had told Fairless in person.

Which was: “I would do it again, for sure.”

Faulkner shared a lot about his past with Fairless. For example, that at a fairly young age, he realized he was developing sexual interest in those quite a bit younger than him.

“I have much younger sisters than myself. They’d never been on my radar, but their friends certainly have.”

Around the age of 13 or 14, Faulkner said he babysat and sexually molested a four-year-old family member. (That abuse went on for years, until Faulkner was in his late teens.) He also began looking for material online, and slowly built a collection on encrypted hard drives.

He spent a lot of time at the local YMCA as a lifeguard, where he got to work with kids every day. Faulkner insisted that at no point while he was working at the YMCA did he ever do anything criminal — but he admitted he pushed boundaries.

Faulkner gave a 12-year-old girl and her two siblings a ride home from the YMCA once, which led to more rides home, as well as trips to the beach and going out to eat — all without their parents’ knowledge.

One night, he began texting the 12-year-old from a bar, and received a response suggesting they meet in an isolated spot on the town’s lake shore. When Faulkner arrived, the girl’s mother, grandmother and uncle were there. They had intercepted the messages.

“They are like, you are going to stop this, and I’m like, yes, I’m going to stop this.”

Faulkner said he felt “traumatized” by the close call and decided to contact a psychologist. He spoke with one, but said that when he confessed that he liked young children in a sexual way, the psychologist told him he should “just deal with it.” Although Faulkner had only approached one therapist, he felt the entire psychological community had failed him.

Even so, Faulkner clearly had no qualms about exploiting children. He had hard drives of child pornography. He admitted to Fairless that even if he had found a psychologist more willing to help him out, he didn’t think he would have had the strength to get rid of his pictures and videos.

Despite dozens of hours of conversations with Faulkner, Fairless said it wasn’t until the second sentencing hearing that he learned the full extent of Faulkner’s involvement on the dark web.

The prosecution had called an expert witness from the U.S. Department of Justice who gathers digital evidence to prosecute people like Faulkner and had gained access to private encrypted messages between Faulkner and Falte.

Faulkner wrote about the power he felt from running these sites.

“Keeping secrets makes me feel like a bad ass," he wrote to his friend. “Running child porn sites, having most of the market. LOL.”

Find out the true extent of Faulkner's crimes on Episode 6 of Hunting Warhead:

The court also heard that Faulkner was the administrator for a site called Private Pedo Club and ran a website with a focus on children’s feet.

This meant at the time of his arrest, Faulkner was running at least four child abuse sites under various user names. Høydal, the Norwegian journalist, added that Faulkner was also working as the tech expert for an Australian who ran a group called No Limits Fun, which abducted and sometimes purchased children to torture them and record it. One of the children was killed as a direct result of this abuse.

A recent study by the Canadian Centre for Child Protection found that 70 per cent of people whose abuse as a child had been shared over the internet lived in constant fear of being recognized. In fact, 30 per cent of them had been recognized by someone who had seen images of their abuse.

Along with staggering rates of anxiety, depression, eating disorders, problems sleeping and relationship issues, 60 per cent of the respondents had attempted suicide.

VI.

When he was arrested in October 2016, Faulkner gave up all his passwords and codes. On the other side of the world, Australian police officers Paul Griffiths and Jon Rouse sprang into action.

In addition to being members of the Queensland Police Service, Griffiths and Rouse were part of Task Force Argos, a world-renowned unit investigating online child exploitation and abuse.

Their mission was to take over Childs Play — as Warhead — and keep it running in order to gather as much information as they could about its clientele and users who were producing new pornographic material.

Assuming Faulkner's role was a significant challenge. Any indication that the site had been compromised by police would tip off its million-plus users, prompting them to delete their accounts and scatter to other parts of the dark web.

Faulkner had developed a protocol to ensure the site couldn't be taken over by an undercover unit — something he called a “canary.” Warhead had told the community that at the beginning of every month, he would post a message sharing some information about the status of the forum. If the message wasn't posted, the community was to assume that Childs Play had been compromised or taken over by police.

Homeland Security had arrested Faulkner on Oct. 3, but Warhead was expected to post a canary the next day. Griffiths poured over Warhead’s posts, studying his spelling errors and punctuation and mastering his style, linguistic quirks, even his sense of humour.

Four days after Faulkner's arrest, Griffiths brought Warhead back online with this message:

"Phew, what a month. That was a month of my life that I won't get back. Although technically most of the really screwed up shit happened in October, not September. Hence my late foray into this month. Sorry again about the late arrival, but I did ask the staff team to step in and cover for me in my enforced absences.”

Griffiths believed at least one or two of the users had strong suspicions that something wasn’t right. It was the job of other undercover agents, posing as users, to quiet down those rumours.

Listen to the third episode of Hunting Warhead, in which Taskforce Argos assumes Faulkner's dark net alias:

By the end of October, Childs Play had been successfully transferred from the server in Australia to one in Europe. Despite the initial suspicions, it seemed the majority of the site's users believed Childs Play was safe and secure.

Over the next months, Task Force Argos monitored activity on the site, trying to identify new material and people who were either producers or close to the production of the material, and try to identify the children in the pictures.

Høydal, the Norwegian journalist, said that investigators asked him not to publish anything during this time. He and his editors at VG reluctantly agreed.

Investigators said they would keep Høydal in the loop about numbers in terms of arrests or children saved, but that never really happened. In mid-September 2017, Stangvik discovered on his own that Argos had shut down the site two days earlier.

VG published Høydal and Stangvik’s story about the police's operation as Warhead on Oct. 7, 2017, but it wasn’t until August 2018 that Task Force Argos put out a press release stating that their detectives had contributed to the removal of 83 children from sexual harm internationally, and arrested 200 child sex offenders.

Task Force Argos had operated Childs Play for 11 months, nearly twice as long as Faulkner himself. The evidence Argos gathered led to more than 300 new police cases around the world.

"It's almost like you're encouraging the users to abuse children.”Høydal and Stangvik were concerned about the ethics of maintaining a child porn site, even as a snare for offenders. "It's almost like you're encouraging the users to abuse children,” Høydal said.

Carissa Hessick, a law professor at the University of North Carolina and an expert in child pornography laws, said police can’t really know if running an operation like this will actually free a child. Another problem, she said, is trying to determine when these undercover investigations should end. For example, undercover agents who have infiltrated the mob set limits for when they have to wrap up an investigation.

"If the site is being used to facilitate the actual abuse of children and law enforcement is continuing to run it, then I have real questions about their ability to strike this balance,” Hessick said.

At least one person, however, has no ethical worries about it. Jen, whose family Faulkner victimized, said she has no problem with the methods utilized by police.

“The images are already out there. They're already there. Why not utilize this and catch more of these guys?”

She acknowledged that her kids’ images are among them. “Yes … That's horrible. But holy moly, if we can catch that many people doing this? Catch them. Catch them.”

Source : https://newsinteractives.cbc.ca/longform/hunting-warhead-child-porn-investigation